Véto-pharma

Véto-pharma The Yellow-legged hornet (Vespa velutina, also called “Asian hornet” in Europe), often mistaken for its larger cousins (Vespa crabro and Vespa mandarinia), has been making a global buzz. Originally from China, it began its Western march by invading France in 2004 and has since spread throughout Europe. Now, it’s taking flight in the US, posing new challenges. However, it’s not an unbeaten path. French beekeepers have faced this threat for many years, gaining invaluable insights into the Yellow-legged hornet’s behavior and ecology. With the support of Véto-pharma, they’ve gathered the knowledge and tools to tackle this intruder. Together, we’ve accumulated a broad understanding of the Yellow-legged hornet, which we’re eager to share with the American beekeeping community.

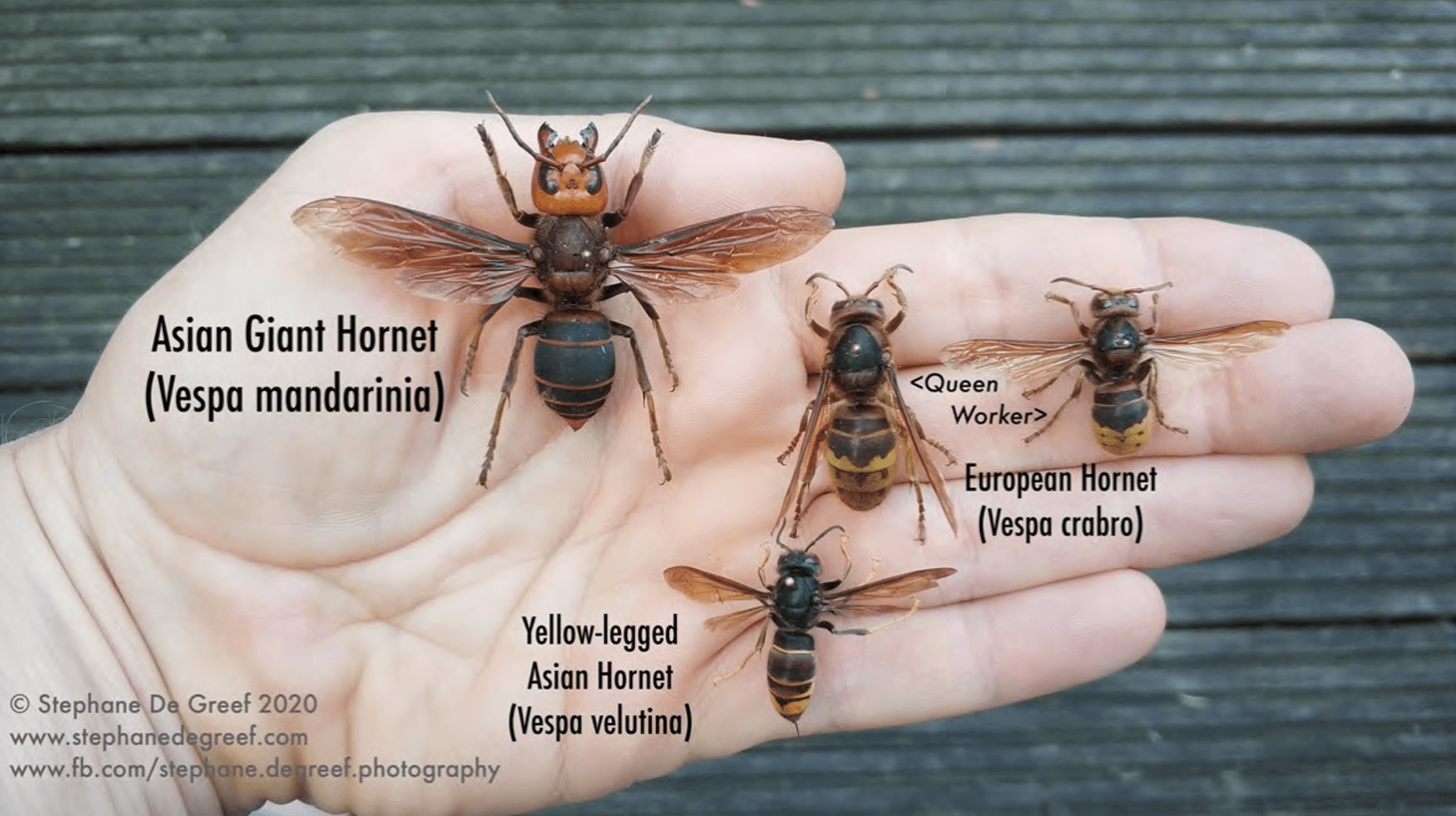

Slightly smaller than its European cousin and much tinier than the Asian Giant Hornet, Vespa mandarinia, the Yellow-legged hornet stands modest at about 2-3cm [0,78-1,18 inches]. Sporting a mostly black abdomen with a standout yellow fourth segment, it’s rightly dubbed “the yellow-legged hornet”. Its vibrant yellow-orange face further sets it apart. Spotting this winged invader is step one to safeguarding our ecosystems.

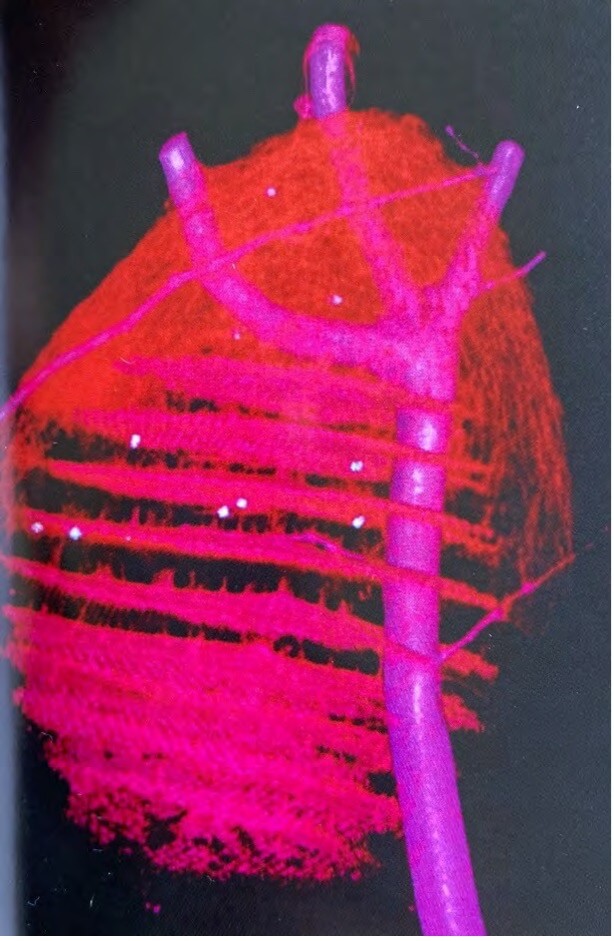

Imagine a delicate paper structure crafted from chewed wood pulp and saliva. That’s an Yellow-legged hornet’s nest for you!

In the early stages, the primary nests whipped up by the queen (termed “foundress”) from March to June are small, about the size of a mandarin. Built with a trio of protective layers, these nests have their entrances at the bottom and snuggle up in sheltered nooks such as shrubs or trees.

But here’s where things get grand. As summer hits its stride, Asian Hornets either upscale their primary real estate or go house-hunting for a spacious new home. Mature nests, often nestled high in tall trees, are marvels of natural architecture. Towering up to a meter [40 inches] in height, they prefer the serene ambiance of watersides, like riverbanks. Fun fact: these nests are exclusive nursery chambers for their brood – no food storage here.

By year’s end, nests boast a whopping 12,000 cells but dwindle to a modest 2,000 members come October. To thwart their expansion, savvy French beekeepers deploy “spring trapping” techniques. But hang tight, we’ll delve deeper into this in a forthcoming article.

The life of a Yellow-legged hornet revolves around four main stages: the egg, larva, pupa, and the adult. Here’s a look into their fascinating life cycle (depending on the state and climate you live in, months may vary):

The siege of the Yellow-legged hornet, in summer-fall, is a challenging period for bee colonies. Worker hornets hover at hive entrances, effectively blocking bees from venturing out. As a result, bee activity reduces drastically, affecting their ability to gather nectar and pollen. This not only depletes their food reserves, jeopardizing their winter survival, but also induces stress. Studies have indicated oxidative stress in bees during hornet predation, leading to premature aging. It’s noteworthy that hornets don’t discriminate; they target all hives in an apiary without preference.

Feeling enlightened? Stay tuned as we discuss the French beekeepers’ decade-long battle against the Yellow-legged hornet and guide you on spotting and decimating nests.

In the meantime, why not test your new-found hornet wisdom? Dive into our Yellow-legged hornet quiz and see if you’re geared up for the hornet showdown!

Join the Véto-pharma community and receive our quarterly newsletter as well as our occasional beekeeping news. You can unsubscribe at any time if our content does not suit you, and your data will never be transferred to a third party!

© 2019-2025, Véto-pharma. All rights reserved