by Antonio Pajuelo

by Antonio Pajuelo Hornets are distant relatives of bees, having evolved from a common ancestor. They undergo a very similar life cycle, progressing through egg, larva, and pupa stages before becoming adult insects. Some species, like the Ichneumonidae, play beneficial roles by laying their eggs on the caterpillars of other insects, thus helping to control their populations. This has led to their breeding for biological pest control. Others lay their eggs in vegetation, causing the formation of galls. But unfortunately, others cause a major threat to honey bees and other pollinators, making the life of beekeepers a living hell.

Hornets vary from solitary to social in their behavior. They have a diverse diet that includes both vegetarian (nectar and pollen) and carnivorous preferences, with the latter sometimes leading to interference with bee populations. Typically, they favor dry and warm environments with some vegetation cover. Their life cycle witnesses a population growth in spring and summer, preparation for hibernation in autumn, and, with the arrival of cold weather, reproductive females seek shelter for hibernation, leading to the disappearance of their nests and workers.

The native hornets in our region [Western Europe] usually do not have a harmful effect on bees. Except, perhaps, Vespa crabro, which is generally uncommon but, in some areas, may steal some honey in the fall as they prepare for hibernation. It can be identified by its large size, about 3 cm, the arrangement of yellow and dark bands on its abdomen, and its reddish-colored thorax and head. Their nests usually have entrances at the bottom.

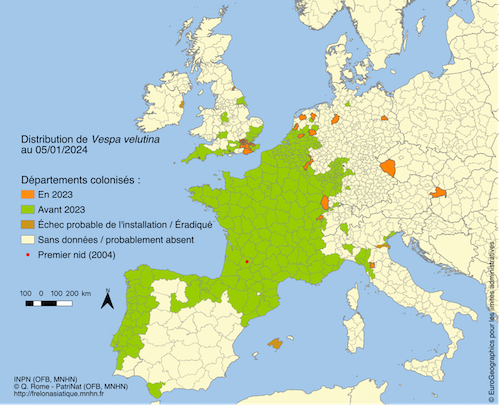

In recent years, Vespa velutina, a species particularly dangerous to bees, was introduced in Western Europe (and recently spotted in the USA). Originating from Asia, it was first observed in 2004 in Bordeaux (France) and has since gradually invaded the whole country, reaching Spain through the Basque coast in 2010. It preys on bees for sustenance.

Additionally, new species such as Vespa bicolor and Vespa orientalis have been spotted in Andalusia, Spain (Cadiz, Malaga, and Jaén) between 2017 and 2018. Moreover, Vespa mandarinia, also known as the Asian giant hornet, has been observed at the border of the USA and Canada in 2019.

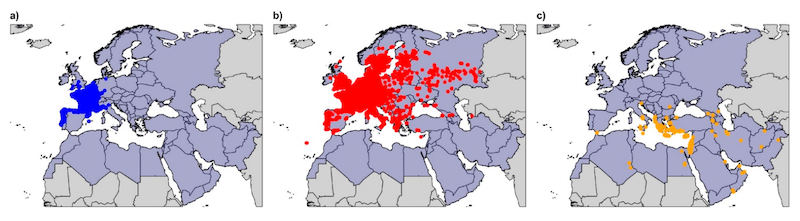

In the attached images, you can see the distribution of Vespa velutina nigrithorax (a), V. crabro (b), and V. orientalis (c) in Europe and North Africa. The temporal range of the data is 1990-2021 according to Lioy S. 2023.

Undoubtedly, Vespa velutina presents the most significant danger to bee hives and humans. Queens emerge from hibernation to construct their nests from cellulose derived from deciduous tree leaves, where they lay their first eggs. They then hunt to feed their larvae. Once the first workers hatch, they take over the tasks of nest expansion and hunting, allowing the queen to concentrate on egg-laying.

Large, about 3 cm in size, with queens slightly larger than workers when fully developed, Vespa velutina is identifiable by the arrangement of yellow stripes on its abdomen, a black thorax, and the outer half of its legs being yellow. Their nests typically have entrances towards the center. By autumn, the nest can reach up to 1 meter in height and house around 3,000 hornets, including new queens and males. The onset of winter sees the fertilized queens seeking shelter to endure the cold, while the workers perish and the nest disintegrates.

Vespa velutina‘s spread has been significant, particularly along coastal areas with Atlantic climates, which closely resemble its native habitat. This environment, characterized by high humidity, dew, and moderate temperatures, supports the growth of deciduous trees, providing the hornets with the necessary cellulose to construct their nests. The presence of Vespa velutina has resulted in considerable damage to beehives, especially in regions with numerous small apiaries. A nest established nearby can lead to the daily predation of bees, with potential losses ranging from 30% to 50% of hives over a year.

Areas highlighted in green indicate regions where Vespa velutina had been observed prior to 2023. Regions marked in orange represent new territories colonized by Vespa velutina in 2023.

In Mediterranean climate zones, apiaries are often larger, and beekeepers frequently relocate them, depriving the hornets’ nests of their hunting grounds. Moreover, the foliage of trees such as oaks is tougher, and winters are harsher (particularly in continental Mediterranean regions), which constrains the spread of Vespa velutina.

The effect of Vespa velutina on bees extends beyond mere predation. The simple presence of hornets fluttering in front of the hives activates the bees’ survival instincts, deterring them from exiting the hive. It is a common sight to observe hive entrances sealed with propolis to narrow the opening, with bees scarcely emerging, thus avoiding leaving the hive. The presence of 10 Vespa velutina individuals at the hive entrance can reduce bee activity by nearly 100% (Diéguez-Antón, 2023, Communication XI Congress of Beekeeping, Malaga).

Such circumstances induce stress in bees, a condition shown to adversely impact their health (Leza 2019). There is an increase in the expression and activity of antioxidant enzymes and more significant lipid oxidative damage in colony members exposed to this predator.

The consequences of this stress on the colony are immediately apparent: the queen ceases egg-laying, and the hive’s reserves are depleted. Foraging bees refrain from venturing out, and those that do often fail to return.

To combat this, the most prevalent method currently employed involves placing traps baited with attractants in locations where nests have been identified, as well as in the vicinity of the apiary, at the onset of spring. The Velutinas captured during this period are typically queens, thereby diminishing the potential for nest establishment in the area. Research is ongoing into more enticing Velutina pheromones and innovative trap designs to enhance their selectivity and efficacy.

As the year advances, the traps will primarily capture worker Velutinas. During this stage, in addition to using traps, it is strongly recommended to employ protective measures within the apiary to thwart Velutina attacks on bees and reduce their numbers as much as possible. Examples of such protective devices include protective shields and electric harps.

In France, it is widely acknowledged that the risk of bee colony mortality attributable to Velutina could affect up to 29.2% of beekeepers’ livestock at the national level. The financial repercussions of such colony losses could ascend to approximately 30.8 million euros annually, equating to an economic burden for beekeepers that corresponds to losing 26.6% of their honey income.

Velutina exhibits poor tolerance to cold (Shantal, 2018), suggesting that relocating to higher, colder regions during their nest-building season—from late spring through summer and into autumn—could be an effective strategy in densely populated areas. Nonetheless, climate change is facilitating Velutina’s adaptation to new environments.

The duration of Velutina’s impact on beehives ranges from 5 to 9 months, varying by location. While the ideal temperature for Velutina lies between 16-20°C, they have been observed in conditions ranging from 5 to 38°C (Diéguez-Antón 2022).

In 2022, the company Tragsa eradicated 25,000 Velutina nests in Galicia, yet estimates suggest the actual number could be triple that amount. Velutina accounted for 6% of emergency service (112) calls, with some instances leading to human fatalities. This underscores the importance of community involvement in identifying nests and coordinating trapping efforts for the subsequent year.

Ongoing efforts aim to discover effective nest removal techniques that minimize environmental harm. To this end, a research team at the University of Tours has been exploring the use of steam vapor.

Vespa orientalis, indigenous to the entire eastern Mediterranean, is a nomadic wasp that has exploited international transport to expand its territories, even reaching Chile in 2018 (Ríos et al., 2020). Italy’s experience is noteworthy, with the wasp first recorded in the south, but since 2018, nests have begun appearing, and specimens have been sighted in many other areas (See map of current distribution).

Romania reported at least one nest in Bucharest in 2020 (Zachi & Ruicănescu, 2021), while multiple specimens were observed in the Marseille area of France in 2021 and 2022.

In Spain, it was initially identified in Valencia in 2012 and later in Algeciras in 2018, from which it spread to the provinces of Cádiz, Málaga, Sevilla, Jaén, Huelva, and Córdoba. Notably, it was also cited in Madrid in 2020, within the warehouses of a shipping company (Castro, del Pico 2021), and in the port of Barcelona in 2022 (La Vanguardia).

Given its distribution, Vespa orientalis appears well-suited to dry and hot climates, making its settlement along the Mediterranean coast and the southern parts of the Peninsula likely (Castro, 2021).

This hornet is distinguishable by its reddish or reddish-brown head, body, and legs, with large yellow spots on the face and two bright yellow stripes near the abdomen’s end. It is a medium-sized wasp, marginally smaller than Vespa crabro.

In temperate zones, nest populations peak in autumn, reaching up to 400 individuals. This period marks the greatest nutritional demand, as the colony must support the males and future queens. Nests are predominantly located in buildings, though they are also found in natural crevices, trees, and rocks.

Vespa orientalis‘s diet mirrors that of Vespa velutina, including sugars from nectar, sap, or honey, and fruit, which they can access by tearing the skin with their mandibles. They also hunt other insects for protein.

Although some beekeepers in Andalusia report significant damage to hives in small apiaries and stands, there are no comprehensive studies to quantify this impact. Similar to Vespa velutina, Vespa orientalis poses a threat to biodiversity, affecting both flora and fauna in its settled areas. Instances of stings to humans have been reported in the provinces of Cádiz and Málaga.

Vespa bicolor is distinguished by a distinctive clear shield on its thorax, earning it the nickname “black shield wasp.”

This species is social in nature but is notably smaller and more yellow than the Vespa velutina. Native to China, it has successfully adapted to a variety of microclimates, showing a preference for humid subtropical environments. In Spain, Vespa bicolor has been documented since 2013, but its presence is confined to just three municipalities within the province of Málaga.

An observed nest (Castro, 2019) was situated under the protection of an eave, suggesting that, similar to other hornets in its family, Vespa bicolor sustains its offspring on a diet of sugars and proteins. Despite its presence, the expansion of Vespa bicolor does not currently pose a concern, nor does it have a measurable impact on beekeepers or the environment.

Characterized by its gentle nature, Vespa bicolor is not known for aggressive stinging behavior, indicating minimal risk to humans in its vicinity.

As we navigate the evolving landscape of invasive Vespa species, the future remains uncertain. The introduction of species such as Vespa velutina, Vespa orientalis, and Vespa bicolor presents both challenges and opportunities for understanding and managing their impact on local ecosystems and bee populations. It is imperative that we continue to monitor these developments closely, employing scientific research and community engagement to devise strategies that mitigate risks while preserving biodiversity. Proactive measures, including further study of these species’ behaviors, habitats, and ecological effects, will be crucial in crafting informed and effective responses. In this way, we can hope to balance coexistence with these invasive species and the protection of vital pollinator communities essential for our natural world and agricultural systems.

by Véto-pharma

by Véto-pharma  by Véto-pharma

by Véto-pharma Join the Véto-pharma community and receive our quarterly newsletter as well as our occasional beekeeping news. You can unsubscribe at any time if our content does not suit you, and your data will never be transferred to a third party!

© 2019-2025, Véto-pharma. All rights reserved