par Juan Molina

par Juan Molina As the beekeeping season moves along, a colony’s preparation for winter starts long before the first frost. While this article focuses on winter practices, it’s important to remember that getting ready for winter is a year-round effort. A colony that faces stress or poor conditions earlier in the season will struggle to produce the strong, healthy winter bees needed to survive.

The real push for winter begins in late summer, when bees start raising specialized “winter bees” that will keep the hive going through the colder months. As days get shorter and temperatures drop, this preparation becomes more visible. For beekeepers, this means staying alert throughout the season, especially during key moments when new generations of bees emerge.

By considering the beekeeping season in its entirety and focusing on these pivotal moments of generational change, beekeepers can help their colonies enter winter with robust, healthy bees capable of surviving until spring. From spring build-up to summer honey production and into winter preparations, every part of the year plays a role in setting the colony up for success.

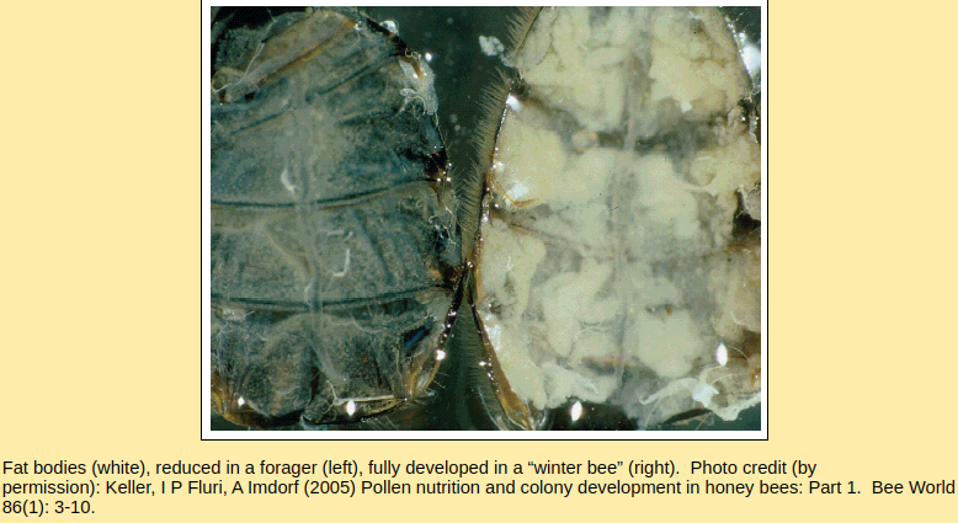

Winter bees exhibit a markedly different physiological profile compared to their summer counterparts. Their bodies accumulate greater fat reserves (Brejcha, 2023)1, a larger quantity of proteins, including vitellogenin (Amdam, 2005)2, their hypopharyngeal glands are less active and the bees have a reduced tendency to fly (Cormier, 2022).3 These adaptations enable them to survive for several weeks inside the hive, sustaining the colony during the winter months.

When the outside temperature drops below 15ºC (59°F), the bees form the winter cluster (Southwick, 1987)4, an ellipse-shaped grouping (Owens, 1971)5 with little to no brood at the center. By vibrating the muscles in their thorax, bees generate body heat, maintaining a temperature of 30.4–36ºC (86.7–96.8ºF). This translates to an average cluster temperature of 21.3ºC (70.3ºF), with the center being much warmer (27–35ºC = 80.6–95ºF) than the edges (Stabentheiner, 2010). 6

This process requires heat generation, which in turn consumes carbohydrates as the primary energy source. Therefore, one of the beekeeper’s main tasks during winter is to ensure sufficient sugar reserves, either from produced honey or supplemental food.

The colony size required to sustain winter temperatures is vital. An insufficient “critical mass” of bees will fail to maintain minimum temperatures. Conversely, highly developed colonies, while better at generating heat, consume larger amounts of food. The severity and duration of winter are also important factors.

During autumn preparations, beekeepers should merge colonies that do not meet minimum size requirements. Apiary growth depends on bee health and numbers, not hive quantity.

Colonies must enter the autumn period free from diseases. Varroosis, the primary disease affecting honey bees (Van Der Zee, 2015)10, increases energy expenditure, reduces survival rates (Aldea, 2019)11, and often exacerbates other pathogens (Martin, 2001)12, such as viruses. The disease impacts fat body reserves and vitellogenin levels, weakening the bees’ immune system. Monitoring hive health after autumn treatments and before wintering is, therefore, critical. If mite levels remain high as the colony heads into winter, an oxalic acid treatment is strongly recommended to reduce the mite load and improve colony survival chances.

When evaluating food reserves, consider not just quantity but quality and placement:

– Avoid placing food bags too far from the cluster.

– Openings should be wide enough for bees to access.

– Prevent food from becoming overly fluid (at 18ºC, or 64.4ºF), as this can wet the bees and cool the cluster.

Best feeding tip: Place the food where it’s easy for the bees to reach, ideally right over the brood area. Make sure the opening faces down, and be careful to avoid spills on the frames or the bees.

Visits should be minimal during winter. Ideally, only open hives on sunny days when outside temperatures exceed 16ºC (61ºF). Always work quickly to minimize disturbance to the colony and avoid removing frames to prevent chilling the brood.

Winter is also a preparatory period for beekeepers. Tasks such as scheduling apiaries, cleaning hives and frames, and preparing wax can be completed in advance for the upcoming season.

Overwintering honey bees is no simple task. It’s a delicate balance of individual bee traits, colony behavior, and external stressors.13 While we know a lot about major culprits like Varroa destructor mites and pesticides, the impact of other factors—like climate change—remains less clear.

There’s still a lot to learn, especially when it comes to how multiple stressors interact and how colonies behave during the winter months. Traits like population size, honey reserves, and social thermoregulation are key indicators of winter survival, with social thermoregulation showing particular promise as an early warning sign for potential trouble.

What’s clear is that stress factors can disrupt the colony’s ability to stay balanced. If the challenges become too much, they can push the hive past a critical threshold, leading to losses. More research into these areas could help beekeepers better monitor their hives and develop strategies to reduce winter losses.

References:

Image banner : © Liubovyashkir

by Juan Molina

by Juan Molina  by Véto-pharma

by Véto-pharma  by Véto-pharma

by Véto-pharma Join the Véto-pharma community and receive our quarterly newsletter as well as our occasional beekeeping news. You can unsubscribe at any time if our content does not suit you, and your data will never be transferred to a third party!

© 2019-2025, Véto-pharma. All rights reserved